|

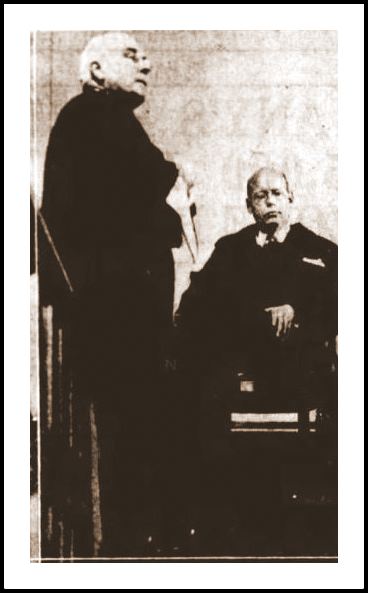

| Judge Seabury and Fred French in court, November 16, 1931. |

Fred F. French had always been a straight-and-narrow kind of fellow. He prospered on his ambition and his clean living; he was a great man for pep talks and inspirational meetings. His treatment by the press was equally positive.

Then Judge Samuel Seabury ordered French to testify about a fee paid to a law firm that persuaded the Board of Standards to rule in his favor. To French, it was a common enough business practice; to Judge Seabury, it was against the law. An eyewitness wrote:

French was, from a coolly scientific viewpoint, a highly amusing witness. His antics were those of a Wagnerian prima donna with a burr in her seat. He felt in the episcopal Seabury a subtle lack of appreciation for his position as a leading citizen of the community. . . Any intimation that he had bought political pull, French was convinced, might place him in a bad light before the general public and cast doubt on his moral fervor. This, of course, was arrant foolishness; in New York the ownership of one million dollars is, very sensibly, an automatic certification of good character and moral infallibility.

French was angry when he took the witness stand, and he was angry and almost apoplectic when he stepped down. He started the day in a jolly fashion by refusing to waive immunity from criminal prosecution. . . The investigative committee permitted French to retain his immunity, and the questioning, marked by frequent outbursts of temperament, proceeded. The witness resented the questions, and he resented the newspaper cameramen present.

French ended the day facing contempt of court charges when he refuses to answer questions.

|

| Headline of Brooklyn's Standard-Union, November 17, 1931. |

The following day, the papers spun the story as they will, with one journal in Brooklyn giving it front-page treatment, above. Suddenly aware that he had gone too far, French apologizes for his earlier statements, and eventually was excused.

Later, the tale reappeared with the publication of The Tin Box Parade in 1934. The story of Seabury's investigation ‒ the 'tin box' referring to where the guilty hid their money ‒ came with a political cartoon on its cover depicting Roosevelt's shoe giving Sheriff Farley's rear end the heave-ho.

A section entitled "The Boy Wonder of Building" is about French's role in the affair. The long quote (above) comes from this book.

Thank you to Brian Thompson for the tip.

I love the photo of William E. Walsh in that hat!

ReplyDelete